Icelandic Folk Music, Past and Present

by Dr. Bjarki Sveinbjornsson

Margaret and Richard Beck Lectures

University of Victoria

March 23, 2009

In my lecture today I will give you some examples of what we in Iceland define as Icelandic folk music, where it comes from and how we perform it today. I will play for you some of the oldest recordings we have on the subject, as well as new recordings that I did for the purpose of this lecture.

As a part of the Nordic countries, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, Iceland was years behind in collecting and publishing a book of folk music. In Denmark we see a publication on the subject in 1812, Sweden in 1814, and Norway in 1840. In Iceland the first main publication on Icelandic music heritage was in 1906.

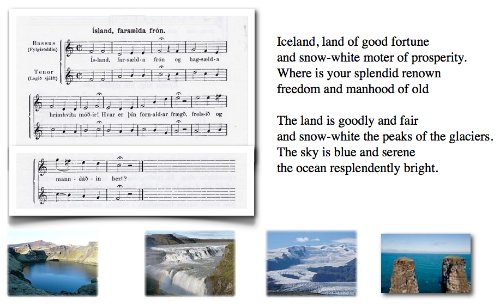

Despite this, five Icelandic songs were published in a French encyclopædia in 1780.

Here you see the first examples we have of printed music with secular texts. Some of the texts are very old—from the Edda poems, perhaps from the ninth to eleventh century, and the music could originate from that time also. If so, we have the oldest examples of music in Iceland.

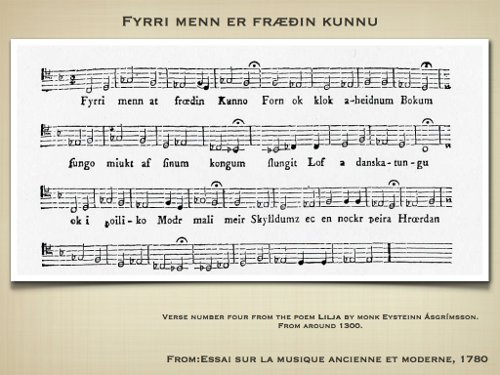

It is important to point out one of those songs which is sung on a poem by the name of Lilja, or Lilly.

This song might be the oldest one known in Icelandic music history, but the poem is from around 1300 written by a monk by the name of Eysteinn Ásgrímsson. It is the last one of five, of the songs from Iceland mentioned in Essai. This melody has been quite a mystery to us; it is an oral dictation by an Icelander by the name of Jon Olafsson, who lived in Copenhagen in the seventeenth century and sang the song to a Danish composer, who wrote it down. That is how it came into the Essay book. The song is in no known key. The melody is quite a strange one, and at the same time, exciting.

The Lilja poem is one hundred verses and the verse we see in the Essay is number four. But usually, when the song is performed today, only the two first verses are sung. The second verse is about when the poet addresses the Queen of Heaven, but the first one, which we will now hear is about the presence of God Everywhere, so, do not follow the text but pay attention to the music.

This was an Icelandic musician and composer that we will hear more about later.

When talking about musical systems, the old church modes that were in use in Europe up to around 1600, were used in Iceland into the nineteenth century. In a book by the title, Icelandic Folkmusic, published in 1906–1909, there are over one thousand songs. Around seven hundred of them are in the old church modes and around 250 in the lydian mode. Due to bad transport in those days, Icelanders did not hear about Diabolus in musica until into the twentieth century.

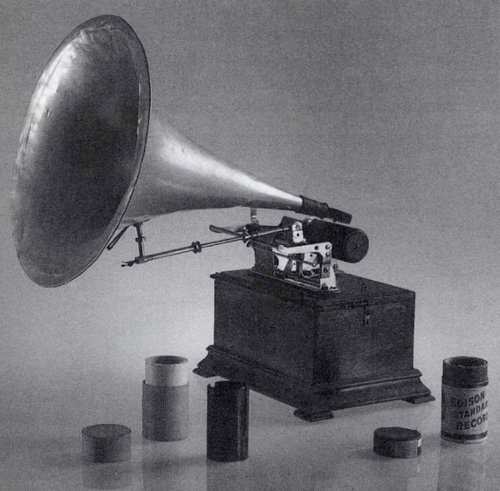

Eddukvæðin

Letʼs talk about poetry. The Edda poems were originally recited from memory before an audience but not written down until later, or around 1200. They fall into two main categories. One deals with mythological subjects and the other with legendary heroes.

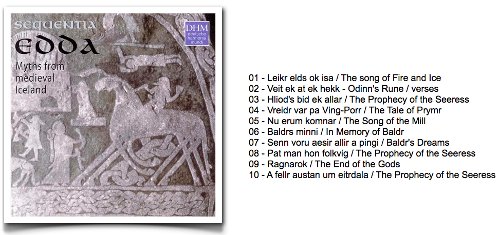

A few years ago, a group of musicians that call themselves the Sequentia Ensemble for Medieval music suggested how those poems might have been performed. After years of study of old historical sources in Iceland, Norway, Ireland, and the Faroe Islands, they came up with this:

Völuspá

As I said, this is only a suggestion, an hypothesis of how it might have sounded originally.

We have to keep in mind that the word singing

first became common in Nordic languages after they became Christian societies—and then mostly in the context of liturgical music.

The word kveða—or recite

is much more common in the secular world, and then especially in the context of rímur, which we will hear more about in a minute.

I will now give you an example of how someone would kveða the Edda poems:

Sveinbjörn kveður

Ríma means literally a rhyme. Rímur are rhymed; they alliterate and consist of two to four lines per stanza. There are hundreds of these meters, counting variations, but they can be grouped in approximately ten families. The earliest rímur date from the fourteenth century.

Rímur evolved out of skaldic poetry with influences from continental epic poems. For centuries they were the mainstay of epic poetry in Iceland. In the large majority of cases the rímur cycles were composed about a subject on which a written story already existed.

In the nineteenth century the poet Jónas Hallgrímsson published an influential and damaging critique on a rímur cycle by Sigurður Breiðfjörð and the genre as a whole. At the same time Jónas and other Romantic poets were introducing new continental verse forms into Icelandic literature and the popularity of the rímur started to decline. Nevertheless many of the most popular nineteenth and twentieth century Icelandic poets composed rímur. In the late twentieth century Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson, whom we just heard, was the best known rímur poet. Steindór Andersen is currently the prevailing rímur singer in Iceland, he sometimes collaborates with the band Sigur Rós.

But the rímur has not always been appreciated—especially not by scholars or the church.

In 1643 a Reverend Sigurður Oddson wrote a letter to his bishop complaining that the sacred writ was faring badly in competition with the impromptu secular entertainment that was practiced outside the churches. People would often leave in the middle of the service to listen to various tales of the heroes. He furthermore complains that one of his parishioners had confided to him that next to hearing about the passion of the Lord he enjoyed nothing more than the rímur.

I myself remember the story of an old lady saying: the Gospels are of no interest if they donʼt have any combats.

The scholar Sigurður Nordal, in the twentieth century, wrote on the rímur:

Icelandic rímur are probably the most absurd example of literary conservatism that has ever been noted. It can be said that they remain unchanged for five whole centuries although everything around them changes. And although they frequently have little poetic value and sometimes even border on complete tastelessness, they have demonstrated with their tenacity that they satisfy the needs of the nation peculiarly well.

Despite this criticism, rímur have gained some popularity again, especially as kind of a remix in popular music, namely by the well-known band Sigur Rós. Let us hear Sigur Rós & Steindór Andersen (A Ferd Til Breidafjardar 1922) Rimur (4:29):

Organized collection of rímur material started in the ninteenth century. Between 1840 and 1850 Pétur Guðjónsson, an organ player at the Reykjavík City Cathedral was commissioned by the Danish composer Andreas Peter Berggreen to write down a collection of folk and rímur songs. The folk songs were published, but as far as we know, the rímur songs never appeared in print.

The first known notation of rímur songs, transcribed by Árni Beinteinn Gíslason, appeared in Ólafur Davíðssonʼs collection of folk entertainment published in the years 1888–1892.

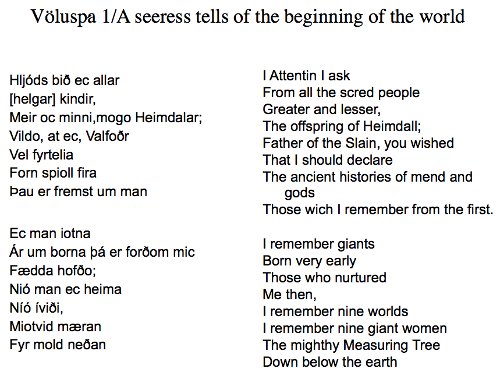

Íslensk Þjóðlög

The contribution by the Reverend Bjarni Þorsteinsson is by far the most significant work in the field. In the late ninteenth century he systematically collected Icelandic folk songs and published them in a 950 page book. The music in the book is of variable interest. The most valuable part of the book is the one on oral transcription from common people from various parts of Iceland, and then, the rímur melodies.

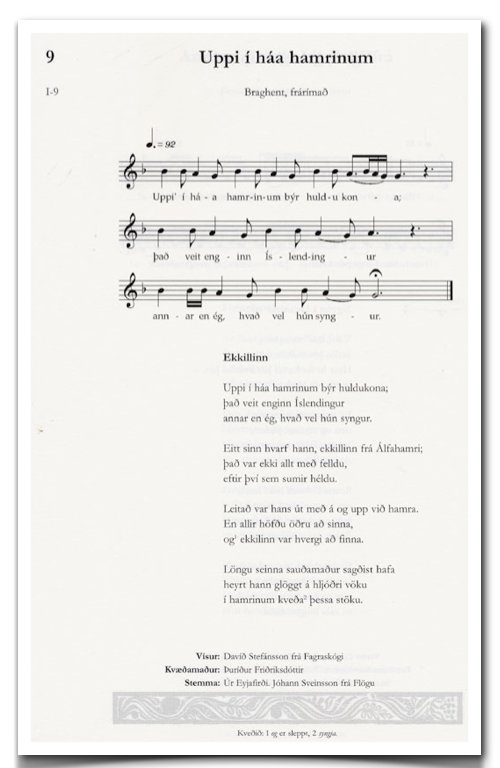

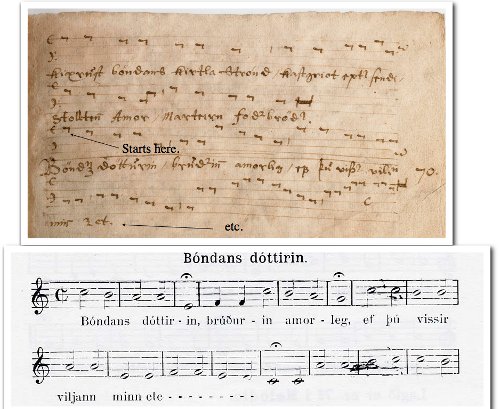

Handrit Bjarna

Reverend Bjarni managed to collect about 250 rímur melodies which are all published in the book. In addition to this, after the recording technology came along, we also know how these were performed in the old times. Here you can see his manuscript, and how it is published in his book.

Jón Pálsson’s Phonograph Cylinder

As in many other countries, the newest technology found its way to Iceland, and once there into the recording technology. As an example of recordings I will mention the composer Jón Leifs.

The composer Jón Leifs records Icelandic folk music in 1934

In 1926, 1928, and 1934 he travelled in Iceland and recorded folk music on cylinders. He followed it up and wrote some articles in a German journal, and even used some of the songs in his compositions and arrangements. I will now play for you one song that he recorded:

Sofðu unga ástin mín.

—úti regnið grætur.

Mamma geymir gullin þín,

gamla leggi og völuskrín.

Við skulum ekki vaka um dimmar nætur.

Sleep now softly little one,

—outside rain is falling.

Mother guards your treasure trove,

Hoard of bones and chest for stones.

We shall not stay awake through nights of darkness.

A mother tells her child to sleep; the weather is bad and the volcanoes are threatening, and she will look after the childʼs toys whilst it sleeps.

Here is a short clip from his arrangement of the same song:

The Iðunn society was estblished in the autumn of 1929. The societyʼs aim was and has been the collection and preservation of the rímur and traditional poetry. Up to this day the members meet once or twice a month and chant for each other, passing the art onto new generations. In the early days, particular melodies were named and documented by linking them to a specific piece of verse. This practice had been taught to some of the members by the older chanters who would catalogue their vast repertoire of melodies by linking them to a signature verse which would serve as a model for all poetry written in the same meter and style. The societyʼs last collection of melodic indicators now counts five hundred examples, all recorded on silver lacquers. Now, two hundred of them have been published in an exclusive collection where all the melodies and word are printed along with four CDs.

Here is an example from this publication:

Hljóðfæri

And now I will tell you a little bit about the oldest instruments. Several old sources mention instruments in Iceland during the Middle Ages. Let us take a look at a few of them:

Symfón

The symfón or symphonie, a medieval forerunner of the hurdy-gurdy, is the first musical instrument mentioned in Icelandic historical sources and is thought to be from the thirteenth century. The last reference to a symphone is from the late seventeenth century: it was owned by Bishop Þórður Þorláksson of Skálholt. The symphonie is mentioned repeatedly in poems and hymns.

In Iceland, interest is growing for musicological studies, and also for old instruments. April 2010 will be the first release of a CD with a group of musicians playing those instruments.

It is actually a music family, who call themselves Spilmenn Ríkínís, or Rikiniʼs players, because Ríkíni was the first known music teacher in Iceland. This musical family performs Icelandic folk music and hymns from the time around and after the Protestant Reformation in 1550. They have been performing for a few years now both in Iceland and in Europe, playing old instruments that are known to have been used in Iceland in former times, for example the langspil, harpa, symfón, and gýgja.

The leaders of this group, Örn Magnússon and his wife, Marta Guðrún Halldórsdóttir, invited me into their home where they performed for me especially for this lecture. Lets hear them perform one of their songs.

Just to mention this Rikini. The Saga of Bishop Jón Ögmundsson, who lived 1052–1121, says as follows:

And he appointed a Français, a seemly priest named Rikini, his chaplain, to teach the art of singing and versification. Rikini was a good cleric. He wrote well, both prose and verse, and so excellent was he in the art of song, and had such a good memory, that he knew by heart all the liturgy for the twelve months, both the day hours and matins, with accurate tone and pitch.

So, already, around 1100 we have a trained musician teaching in Iceland.

Another instrument mentioned in this same saga is the Harp.

Harp

The harpa (harp) is mentioned as long ago as the early medieval poem Völuspá (Prophecy of the Seeress). The first bishop at Hólar, Jón Ögmundsson, later revered as a saint in Iceland, had a harp.

In his saga he says:

Soon at the royal command the harp was brought to the blessed Jón; and having received it he tuned with the highest skill, playing so excellent well that the king and all those who were present rejoiced, understanding that this harp-playing was certainly not composed by mortal men, but emanated from a heavenly hall.

Let us now hear Rikiniʼs players perform on this instrument:

The third instrument I would like to mention as one of the instruments mentioned in the Middle age sources was the Gígja. This instrument better known in the middle ages as Rebec, or Kleingeige in German.

Gígja (Rebec)

The gígja, mentioned in the medieval sagas of Icelanders and in various poetry, was probably the same as the rebec or kleingeige, a stringed instrument played with a bow. An indication of the popularity of the instruments harpa (harp) and gígja (rebec) is that Harpa and Gígja have been popular personal names for women in Iceland down the centuries.

Now the Rikiniʼs players will perform on those instruments together. The song is a little bit funny. It comes from Melodia which is a manuscript containing melodies to both secular and religious songs. The manuscript, which is preserved at the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection (Den Arnamagnæanske Håndskriftsamling) in Copenhagen (Rask 98), is believed to have been written in the mid-seventeenth century. The writer of the manuscript is unidentified.

The text is about the farmerʼs daughter and says something like this:

Farmers daughter

bride seductive

If you knew my will, etc.

Here, the writer does not write out the poem—so we will never know his will.

Fiðlan

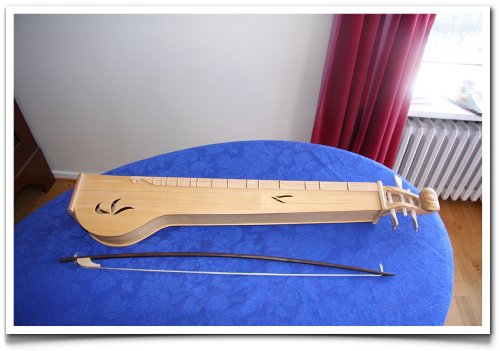

Two instruments are considered as Icelandic

instruments in Icelandic history. One is the langspil and the other one, probably older, is the fiðla (violin).

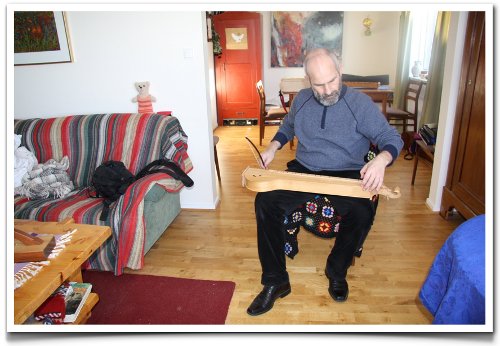

Here you can see this simple instrument. This copy has two nylon strings, but old sources talk about strings made of horse hair. Those two instruments were mainly used to accompany songs, not as musical instruments to play music on. They disappeared slowly from Icelandic culture during the ninteenth century, but in recent years some musicians are bringing this instrument to us again and have trained themselves to play on it.

Langspil and fiðla

The duo is named Funi. Bára Grímsdóttir, whom we heard before is a traditional singer and kantele player. Chris Foster, singer and guitarist, performs Icelandic and English traditional songs and folk songs. Chris Foster will now tell us a little bit about the instrument fiðla.

Langspil

The langspil is often regarded as Iceland’s national instrument. It is a stringed instrument related to such European instruments as the German Scheitholt or Norwegian langeleik. The langspil is played with a bow or by striking the strings with a rod. A considerable number of langspil survive in Iceland.

We donʼt know how far back they were used, but a source from the eighteenth century says as follows:

Now after the eruption I stopped playing musical instruments, due to the manifold melancholy that came upon me.

When on my journey to Setberg, which I have mentioned before, I stayed the night at Bær in Borgarfjörður, I saw a fine langspil hanging there, which the lady of the house, Madame Þuríður Ásmundsdóttir, owned and used. She, who wished to do anything to serve and entertain me, invited me to play. And when I tried, I could not play for my internal grief and thoughts of former times, which she observed, and then began to play herself the most delightful tunes, which revived me and brought me great solace.

The speaker is here referring to the large eruption called Laki that occurred in Iceland in 1783.

Chris Foster will now tell us about his langspil.

And now, Bára and Chris will perform for us, but first Chris will tell us about the song:

To follow up on the langspil I will show you a picture taken in Manitoba in 1875 showing a man with an Icelandic langspil. Some people who emigrated from Iceland to America took their langspil along.

An Icelander holding a langspil in Canada in 1875

And finally on instruments, we hear Rikiniʼs players perform one song on two langspil:

And now a few Icelandic folk songs

Earlier in this lecture we heard an old recording of a song where a mother puts her child to sleep. The song is known in Iceland under at least three melodies, where one of them stands out as a treasure. In my interviews with old people of Icelandic descent here in Canada, some of them knew this song:

That tells us that the song came from Iceland. Maybe some of you know it:

The text of folk music often is about people, feelings, and love, even dead people. The next song is kind of an epitaph:

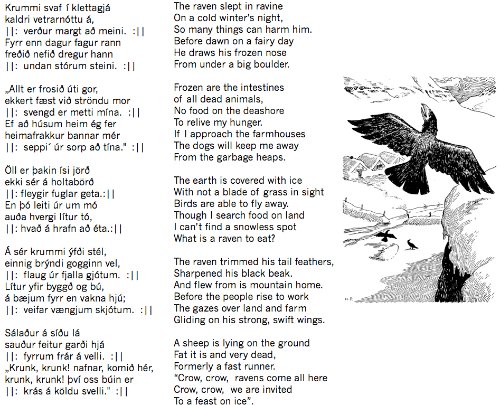

Among the folk songs, we find some that are about birds and animals. Here is one on the raven:

You can find countless poems and songs about love in Iceland. I give you here perhaps the most lyrical one. It is in A-B-A form, and the A part is an old folk song, but composer Jón Ásgeirsson made a middle section, and then did that so well that it makes a perfect love song:

Most of the Icelandic folk songs are single line melodies. There is one exception to this, the so called Tvísöngur, or Two singing. These type of songs are regarded as the most remarkable and distinctive genre of Icelandic music. It is note against note, simple polyphony, characterized by parallel fifth movement and frequent voice crossing. This type of music is found in Icelandic manuscripts dating back to the fifteenth century, and was also a notable feature of musical life in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in orally transmitted forms. Maybe some of you have heard some Tvísöngur, but as the last example on the folk music tradition in Iceland, I will play the best known of them for you.